William Blake and Paul Mellon: The Life of the Mind

CURATOR’S CHOICE #15: MATTHEW HARGRAVES FROM THE YALE CENTER FOR BRITISH ART

Matthew Hargraves, Chief Curator of Art Collections at the Yale Center for British Art, looks at Paul Mellon as a collector of William Blake and the impact of his lifelong fascination with psychology and psychiatry on his collecting.

The Yale Center for British Art holds one of the world’s greatest collections of the work of William Blake thanks to the enthusiasm of its founder, Paul Mellon, for Blake’s art and ideas. Looking back on his life, Paul Mellon remembered that Blake’s “haunting poetry with its arcane mythology and his beautiful illuminated books have always had a special appeal for me,” an appeal rooted in his early passion for English literature which he studied at Yale in the later 1920s.1 But it was the interest of his first wife, Mary Conover Mellon, whom he married in 1935, in thought and methods of Carl Jung that helped transform Paul Mellon into a major collector of Blake’s work.2

Mary had introduced Paul Mellon to Jung’s ideas after they met in late 1933; even before marriage they had begun Jungian analysis in New York. In the early summer of 1938, Mr. and Mrs. Mellon journeyed to Switzerland and spent several weeks in Ascona above Lake Maggiore hoping the mountain air would relieve Mary’s chronic asthma. By coincidence Carl Jung was also in Ascona and the couple met the psychiatrist for the first time that summer. They returned the following year and saw Jung again before settling in Zurich in September 1939 to meet with Jung as patients several times a week. Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939 meant this Swiss idyll could not last. In the spring of 1940 Mr. Mellon took a walking holiday with Jung but the obvious threat from Nazi Germany could not be ignored. He and Mary returned hastily to the United States shortly before the occupation of Denmark, Norway and France in May. By June 1941, feeling compelled to take action, Paul had enlisted in the US army; December saw the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States enter the war.

Fig. 1: There Is No Natural Religion, Plate 9, “Therefore God becomes . . . . ” (Bentley b12), ca. 1788 – Source.

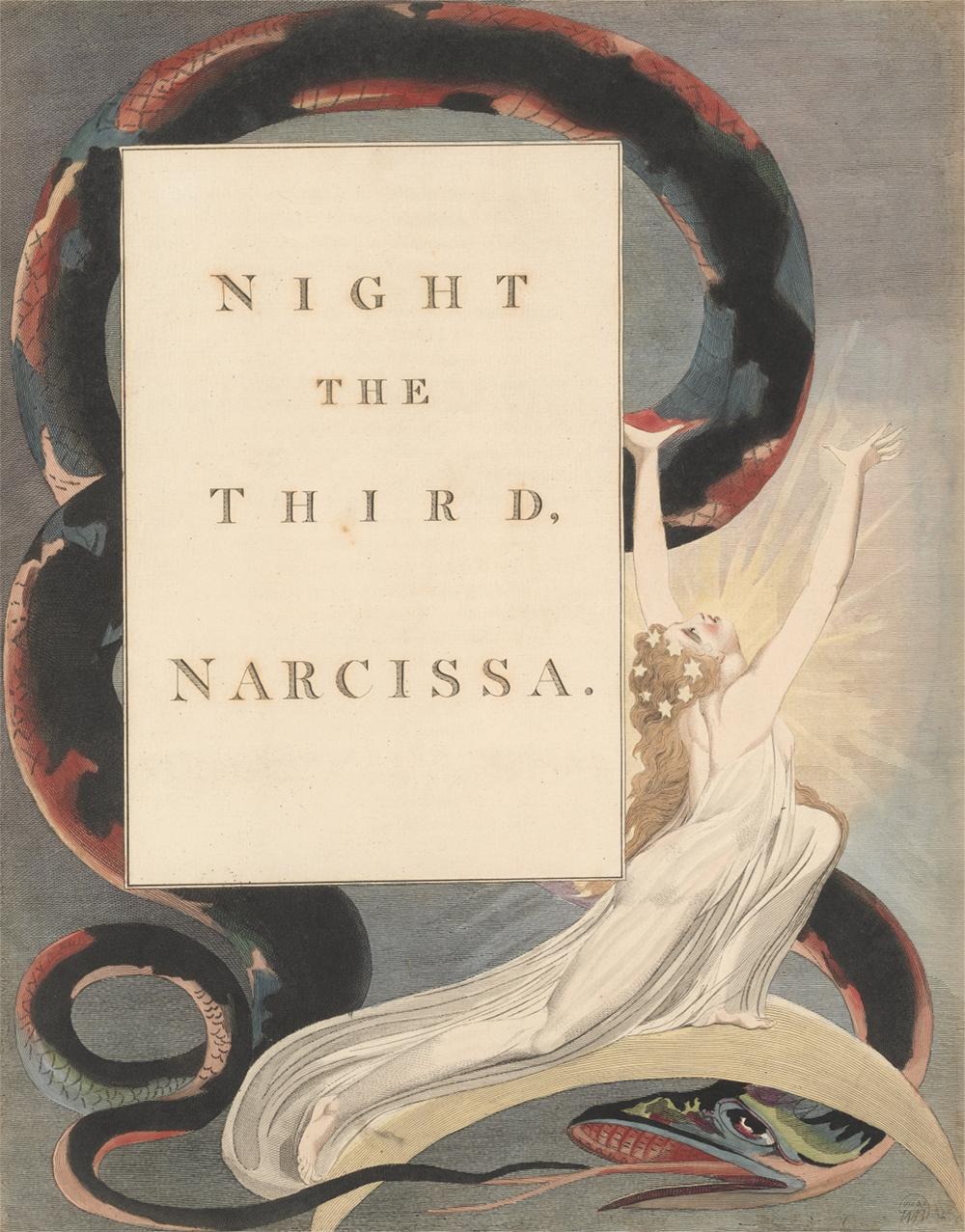

While wartime service forced an end to the relationship with Jung, the year Paul Mellon enlisted was also the year he began to collect important works by Blake, an artist in whom Mr. Mellon found new interest through Jung’s exploration of the unconscious and his theories about collective archetypes. In 1941 he acquired some exceptional books. This included There is No Natural Religion (1794) [fig. 1], an “illuminated” book of eleven color-printed relief etchings with pithy text critiquing the reductive philosophical materialism of his day; a set of the engraved Illustrations to the Book of Job (1825) in its original binding; and a copy of Blake’s engravings illustrating Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (1797) [fig. 2], one of two copies believed to have been hand-colored by Blake himself.

Fig. 2: Young’s Night Thoughts, Page 43, “Night the Third, Narcissa”, 1797 – Source.

Another very significant acquisition in 1941 was a version of Blake’s illustration to The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins [fig. 3], made around 1825 for William Haines of Chichester and one of four replicas of an original design drawn for his patron Thomas Butts in around 1805. Blake adapted the traditional iconography of the judgment of souls to capture the underlying theological meaning of the parable (Matthew 25:1-13), but in the Mellon version the setting has become distinctively English with its distant Gothic spires. It was also one of the first English drawings acquired by Paul Mellon who would eventually form the most comprehensive collection of English works on paper outside of Britain.

Fig. 3: The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins, ca. 1825 – Source.

The enthusiasm for Jung continued despite the war, including an enterprising scheme in the early part of 1945 for Mellon to enlist Jung’s help with psychological propaganda against the retreating German army. Germany’s surrender made the mission redundant and Paul was back home in Virginia by August that year. Almost immediately, and despite Paul’s growing reservations about aspects of Jung’s ideas, the Mellons established the Bollingen Foundation, under the directorship of his their great friend Jack Barrett, with the goal of publishing Jung’s collected works in English translation. But, as Paul Mellon explained later, the foundation’s broader mission was to publish “books devoted to subjects relating to art, aesthetics, anthropology, archaeology, psychology, philosophy, symbolism and comparative religion.”3

At the same time that the Mellons were immersed in the worlds of Jung and Blake, Mary began to form a major collection of alchemical books and manuscripts inspired by Jung’s own collection of similar material. But the return to civilian life was soon clouded by tragedy. In October 1946 after Paul had been home only a year, Mary Mellon died suddenly from an asthma attack. Paul Mellon continued acquiring alchemical material after her death and in 1965 he donated the entire collection of over three hundred items to the Beinecke Library at Yale University.4 From the later 1940s he was also beginning to support psychiatric institutions and therapeutic programs, including the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Hygiene at Yale University, one of the first dedicated departments of psychiatry at a medical school in the country.5

The mid-1940s were a difficult period in Paul Mellon’s life. Looking back he recognized how the destruction and privation he had witnessed in the war had changed him and the extent to which his wife’s death “overshadowed my life for some time.”6 He found solace in collecting, returning to the work of Blake and acquiring important books such a copy of the Songs of Innocence and Experience (1789, 1794) in 1947, the two books bound together in one volume by Blake’s friend George Cumberland; and a copy of Europe a Prophecy in 1948. Blake wrote Europe in 1794 and printed it in 1795, the hand-coloring in Mr. Mellon’s copy believed by some scholars to be the work of Blake’s wife and collaborator, Catherine. This copy was particularly significant for having been in the Disraeli family, bought by Isaac D’Israeli in the 1820s and bequeathed to his son, Benjamin Disraeli, the future Earl of Beaconsfield, in 1848. Europe dealt with that continent’s history from the time of Christ to Blake’s own day, exalting liberty and attacking especially the repressive forces of monarchy and clericalism. Its frontispiece, one of Blake’s most celebrated designs, represents the repressive figure of Urizen compassing the earth, attempting to measure and constrain the infinite [fig. 4].

Fig. 4: Europe. A Prophecy, Plate 1, Frontispiece, 1794 – Source.

In Blake’s complex, personal mythology, the figure of Urizen embodied conformity, and the repressive, rationalist, and materialistic philosophy of the age. Urizen was the enemy of all Imagination, who corrupted the natural ability of people to see things in their true essence. Blake contrasted him to Los, to whom he was once joined, and who represented for Blake the imaginative faculty and the spirit of revolution. Fresh from the horrors of war in Europe, disconcerted by the rising materialist spirit in post-war America, and concerned to help those afflicted with mental illness, Paul Mellon perhaps found resonances in Blake’s impassioned text and images, written as Blake watched the liberating promise of Revolutionary France descend into the bloodshed of the Terror and the spread of war across the Continent.

In the early 1950s Paul Mellon drifted away from Jungian influence and began almost a decade of Freudian analysis in Washington DC, a time he also got to know Anna Freud in London before becoming a significant supporter of her Foundation and what became the Anna Freud Centre for the psychiatric treatment of children. It was in 1953, as he was exploring Freudian psychology, that Paul Mellon bought his most important Blake book, Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion, a book that is at once Blake’s most difficult but also his greatest. He had begun writing Jerusalem in 1804 but had not completed it until 1821 only to find almost no one would buy the epic work. It dealt with the necessary reunion of Albion, symbolizing humanity, with Jerusalem (Albion’s ‘emanation’) representing Liberty and the free exercise of the Imagination [fig. 5]; but so abstruse, complex, and erratic is the text that is has been suggested it may reflect Blake’s own complicated psychological state in his final years, perhaps even schizophrenic tendencies.7

Fig. 5: Jerusalem, Plate 26, “Such Visions Have….”, 1804 to 1820 – Source.

Only five complete copies survive and this unique, hand-colored copy printed in orange ink was retained by Catherine Blake after her husband’s death and was bequeathed to Frederick Tatham when she died in 1831. Tatham was one of the Ancients, the young brotherhood of artists yearning to restore art to its primitive simplicity and who discovered the neglected and penurious Blake in his final years. Tatham had taken Catherine in after William’s death and received from her not only works by Blake but also anecdotes of his life which he wrote down and bound with the Mellon copy of Jerusalem as well as a visionary drawing by Richmond of Blake in youth and old age [fig. 6].

Fig. 6: William Blake in Youth and Age, by George Richmond,

after Frederick Tatham, ca. 1830 – Source.

The enthusiasm and patronage of Tatham and his friends Samuel Palmer and George Richmond rescued Blake from abject poverty and isolation. Most important for Blake was the support of John Linnell, Palmer’s father-in-law and a friend of Blake’s since 1818, who commissioned work from Blake in his last years. Among the commissions Linnell gave Blake was a set of illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy that he began in 1824. This project, consisting of 102 watercolors, was left unfinished at his death. Blake had begun to make seven copperplates after his designs but had pulled only proof states before leaving the drawings and plates to Linnell. Linnell pulled some impressions from Blake’s plates after 1838 and Paul Mellon acquired two sets of the Illustrations to Dante in the early 1960s, which must have had a special significance to him. Mary Mellon had been especially interested in Dante. “Mary” he recalled in 1992, “had made a careful study of Dante’s Divine Comedy while at Vassar (I still have her copy of the book with her assiduous penciled annotations on nearly every page.)”8

By the late 1950s Paul Mellon had begun collecting British art with a new earnestness. His first collecting from the 1930s had been chiefly focused on books and some sporting paintings, but this developed into acquiring paintings and sculpture, as well as prints and drawings. In 1948 he married Rachel “Bunny” Lambert, and the new Mr. and Mrs. Mellon became the foremost art collectors in the United States and icons of elegant and understated style. Naturally his approach to Blake evolved too, with the acquisition of more drawings to go along with the illuminated books and prints. In the 1950s he bought rare landscape studies, and 1961 he acquired Blake’s tempera painting of the Virgin and Child followed the next year by what would become one of his favorite works of art: Blake’s miniature Horse [fig. 7].

Fig. 7: The Horse, ca. 1805 – Source.

This tiny tempera painting was made on a copperplate in around 1805 when Blake was working on illustrations to a new edition of the poems of William Hayley, here illustrating a ballad in which a mother steps bravely between her child and a fierce Arabian horse and tames it.9 Paul Mellon kept it in his Manhattan study until his death in 1999, an object combining his three chief passions for art, literature and horses. But it was in 1966 that Paul Mellon made his most significant acquisition of Blake drawings, buying the Illustrations to Gray’s Poems, a complete set of drawings to the collected works of Thomas Gray. These were made for the sculptor John Flaxman who approached Blake in around 1797 to illustrate Gray’s poetry as a birthday gift for his wife, Nancy. A printed edition of Gray’s poems was dismembered and attached to the center of fifty-eight large sheets of paper on which Blake drew his own designs. Despite illustrating another poet’s work, one of the most striking and characteristically Blakean sheets represents Hyperion, father of the sun, bursting forth to banish darkness and suffering [fig. 8].

The Poems of Thomas Gray, Design 45, “The Progress of Poesy.”, ca. 1797 – Source.

Blake associated the physical sun with Urizen’s corrupt material world, but the spiritual essence of the sun was the province of Los whom Blake associated with Poetic Genius and Imagination.10 For Blake, Imagination was the world of real essences of which the visible world was merely a faint echo. He once argued that “This World of Imagination is the World of Eternity. . . . This World is Infinite & Eternal whereas the world of Generation or Vegetation is Finite & Temporal.”11 Paul Mellon’s interest in psychology is one reason why Blake held such a lifelong fascination given that Blake’s own life’s work was to free the Imaginative faculty from the forces of repression. Despite the incomprehension of his contemporaries and his poverty, Blake kept his devotion to spiritual and mental freedom alive until the day he died. This impulse has remained a vital force long after his death. And in his final months he explained to George Cumberland that his physical body might be “feeble & tottering, but not in Spirit & Life, not in the Real Man The Imagination which Liveth for Ever.”12

Matthew Hargraves is Chief Curator of Art Collections and Head of Collections Information and Access at the Yale Center for British Art. He specializes in British art of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and is the author of Candidates for Fame: The Society of Artists of Great Britain (Yale UP, 2006); Great British Watercolors from the Paul Mellon Collection at the Yale Center for British Art (Yale UP, 2007); Varieties of Romantic Experience: Drawings from the Collection of Charles Ryskamp (YCBA, 2010); and A Dialogue with Nature: Romantic Landscapes from Britain and Germany (Paul Holberton, 2014).

1. Paul Mellon with John Baskett, Reflections in a Silver Spoon: A Memoir (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1992) p. 284. I am very grateful to John Baskett for kindly sharing his knowledge of Paul Mellon’s life and collecting with me, and to Amy Meyers and Scott Wilcox for their careful reading of this article.

↩

2. For the chronology of Paul Mellon’s William Blake collecting I am indebted to Charles Ryskamp, “Paul Mellon and William Blake” in John Wilmerding (ed.), Essays in Honor of Paul Mellon: Collector and Benefactor (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1986) pp. 329-337.↩

3. Reflections p. 172.↩

4. Ian MacPhail and Laurence C. Witten, “The Mellon Collection of Alchemy and the Occult” in The Yale University Library Gazette 41:1 (July 1966) pp. 1-15.

↩

5. Jonathan W. Engel, “Early Psychiatry at Yale: Milton C. Winternitz and the Founding of the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Hygiene,” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 67 (1994) p. 34.

↩

6. Reflections p. 222.↩

7. Robert Essick, ‘Jerusalem and Blake’s final works’ in Morris Eaves, ed., The Cambridge Companion to William Blake (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003) p. 257 ↩

8. Reflections p. 163↩

9. The exact dating of The Horse is uncertain. Though ca. 1805 seems likely, stylistically it resembles work of the 1820s. See Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981) p. ?? no. 366.↩

10. S. Foster Damon, A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake (Boulder: Shambala, 1979) p. 246↩

11. William Blake, ‘A Vision of the Last Judgment,’ in David V. Erdman, ed., The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982) p. 555.↩

12. Robert William Blake to George Cumberland, April 12, 1827, cited in Robert N. Essick, The Separate Plates of William Blake: A Catalogue (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983) p. 122.↩

This post is part of our Curator’s Choice series, a monthly feature consisting of a guest article from a curator about a work or group of works in one of their “open” digital collections. Learn more here.

See this post in all its full page width glory over at The Public Domain Review.