The Forth Bridge: Building an Icon

CURATOR’S CHOICE #22: ALISON METCALFE FROM NATIONAL LIBRARY OF SCOTLAND

Alison Metcalfe, curator in the Manuscript and Archive Collections department of the National Library of Scotland, presents the Library’s collection of photographs recording the construction of the Forth Bridge, the first major structure in Britain to be made of steel and a milestone in civil engineering.

The National Library of Scotland’s collections are rich in visually appealing material, and the volume of public domain collections available online continues to grow steadily. Available via the digital gallery, the Library’s digitised collections cover a plethora of subjects, from Mary Queen of Scots’ last letter, to Scottish theatre posters, and from medieval treasure Murthly Hours to photographs taken at the Western Front during WW1.

One particularly popular set of historic images is our Scottish bridge series, which consists of late-19th-century photographs of the Tay and Forth Bridges. These images illustrate how success and failure went hand-in-hand in engineering during the Victorian era. The photographs of the Tay Bridge were taken in the aftermath of the notorious disaster of 1879, when the bridge collapsed during high winds, sweeping a train and its passengers into the river below.

“Steam engine salvaged from the Tay”; from a series of 91 photographs of the wreckage after the Tay Bridge disaster, commissioned by John Trayner on behalf of the Board of Trade – Source.

A few years later, Philip Phillips’ photographs captured the construction of the Forth Bridge, as its steel superstructure gradually emerged from the Forth estuary. The son of Joseph Phillips, a contractor on the bridge who specialised in ironwork, Philip Phillips reproduced this series of 40 silver gelatin prints in his album The Forth Bridge illustrations, 1886-1887.

Taken by Phillips at weekly or fortnightly intervals, the photographs show close-up and distance views of the superstructure, cantilevers, lifting platforms and viaduct, and include an artist’s impression of the completed bridge.

“General view from back of Newhalls Inn, South Queensferry”. This image, looking north, shows the main towers nearing completion – Source.

Now an iconic part of the Scottish landscape, the Forth Bridge stands as testament to the ingenuity and determination of Victorian engineers, and recently celebrated the 125th anniversary of its opening on 4 March 1890. To mark this occasion, a small exhibition at the Library explores the engineering challenges involved in the construction of the Forth Bridge through a selection of photographs, designs, reports and sketches, including the Philip Phillips photographs from the Library’s digital gallery.

Designing the Bridge

Crossing the Forth had long been problematic for the travelling public in the east of Scotland. Ferries had provided a connection across the river for many centuries, and improvements to piers in the estuary in the early part of the 19th century made it possible for ships to dock irrespective of tides. Alternative crossings were also proposed during this period, with the river surveyed for a tunnel in 1806, and a design for a suspension bridge considered in 1818.

Detail from “Plans and sections for a bridge of chains proposed to be thrown over the Frith of Forth at Queensferry”, James Anderson, 1818.

The real catalyst for the provision of a fixed and reliable crossing came later in the century with the spread of the rail network, as several railway companies vied to provide a seamless rail link from London to the north of Scotland. At the same time, developments in engineering and manufacture of steel meant that dreams of a bridge on the scale required to enable trains to cross the Forth and Tay could become a reality.

Railway engineer Thomas Bouch proposed bridges for both the Tay and the Forth estuaries. In 1873, the Forth Bridge Company was established to build a bridge to Bouch’s design. William Arrol, with a number of successful construction projects already to his name, was appointed as main building contractor. Construction on the shores of the Forth was underway when, on a stormy December night in 1879, Bouch’s recently completed Tay Bridge collapsed with the loss of an estimated 75 lives.

Work on the Forth Bridge was halted immediately, and the subsequent public inquiry into the disaster found the Tay Bridge to be “badly designed, badly constructed, and badly maintained”. Confidence in Bouch was irreparably damaged, and his design for the Forth Bridge was officially abandoned in 1881.

“Fallen girders, Tay Bridge”. The damage to the bridge’s structure is clearly seen in this image, one of the series commissioned after the disaster which show in detail the destroyed piers and girders, wreckage of the train and steam engine and other parts salvaged from the Tay – Source.

When alternative proposals for a bridge were invited, Benjamin Baker and Sir John Fowler submitted a design to the Forth Bridge Company on the cantilever and central girder principle. Fowler and Baker were well-established engineers whose long list of achievements included a substantial role in constructing the London underground rail network.

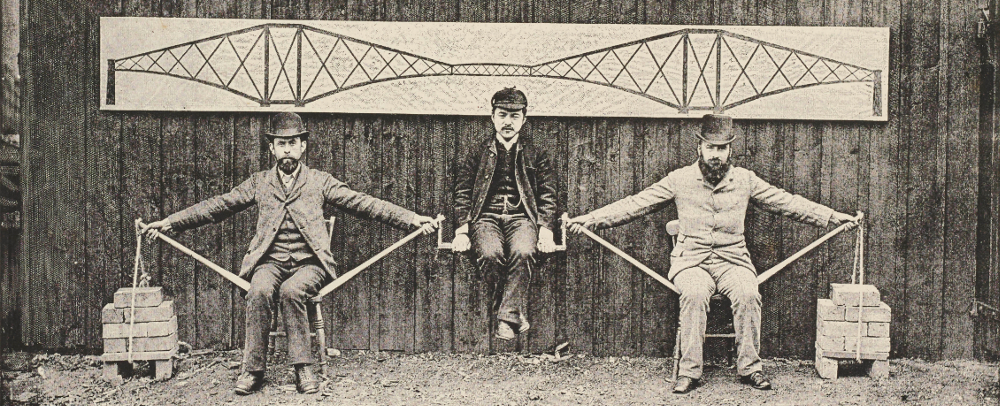

For many years an exponent of the use of cantilevers as the most effective means of constructing long-span bridges, Baker devised the human cantilever to explain the principle at a lecture to the Royal Institution in London in 1887. As he explained, “when a load is put on the central girder by a person sitting on it, the men’s arms and the anchorage ropes come into tension, and the men’s bodies from the shoulders downwards and the sticks come into compression.” The man seated in the centre was Kaichi Watanabe, a Japanese engineer and student of Fowler and Baker who was in the UK to learn Western engineering techniques.

Human cantilever illustration, from “Bridging the Firth of Forth”, Benjamin Baker, 1887.

Foundations

The first major engineering challenge was the construction of the three main stone piers on which the bridge’s superstructure would sit. Half could be built using a dam, where water was excluded from the working area by means of cement bags and liquid grout poured in by divers.

The depth of water and conditions of the river bed at the remaining piers meant that a pneumatic or compressed air method was chosen, using wrought iron caissons to enable men to work below the water level. Once in position on the bed of the Forth, a steel edge at the bottom of each caisson extended seven feet below the concrete filled floor. Water was pumped from the space and replaced by compressed air, creating a small chamber in which men could work. Baker used this diagram of the inside of a caisson to illustrate their operation to his lecture audience at the Royal Institution in London.

Cross section illustrating a caisson, from “Bridging the Firth of Forth”, Benjamin Baker, 1887.

The sinking of caissons was a potentially hazardous affair. One of the Queensferry caissons tilted accidentally whilst being positioned, and the work required to right the cylinder took three months. During this recovery work the caisson ruptured as water was being pumped out, and two men drowned when the damaged structure flooded.

Once the foundations were complete, the masonry piers above the waterline were constructed of Aberdeen granite backed with concrete and rubble, and measured 55 feet in diameter at the bottom and 49 feet at the top, with a height of 36 feet. Each contained 48 steel bolts to hold down the superstructure.

Superstructure

Work on the superstructure began in 1886, starting with the main towers. It was not possible to erect scaffolding, so the structure supported itself and provided a platform for the workmen as the cantilevers gradually extended outwards from each main tower towards its neighbour.

“Fife cantilever with No. 1 strut and lifting platform nearly up to rail level” – Source.

The robust straddle-legged bridge was designed to withstand the enormous pressure placed on it, not just from the weight of trains that would pass over, but from the wind speeds to which it would be subjected. To strengthen the structure further against the wind, the whole was “laced together by lattice girders”, which help give the bridge its distinctive appearance.

“Queensferry cantilever at full height from north end of approach viaduct”. Phillips describes this as “one of the finest in the series”. It shows the construction of the one of the three main towers, and its latticework, in fine detail – Source.

Phillips’ photographs provide an understanding of the means by which the superstructure was assembled, coupled with illustrating the precariousness of the position in which those assembling the superstructure were working. Exposed to all weather conditions and the dangers of working at height, accidents were frequent.

At the peak of activity up to 4,600 men worked on the bridge, though many were employed for very short periods of time. The official figure of the total number of fatalities was 57, though recent research suggests this number should be higher, and many more were seriously injured.

“Birds’-eye view of Inchgarvie and surrounding country”. Phillips took the opportunity of a visit of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers and a period of fine weather to take this shot from the top of the completed Queensferry tower – Source.

Completion

After rigorous testing the bridge was officially opened by the Prince of Wales, who proclaimed that it “marks the triumph of science and engineering skill over obstacles of no ordinary kind.”

At the lunch which followed, the Prince announced that both Benjamin Baker and William Arrol would be knighted, and Sir John Fowler created a baronet, in recognition of their role in the success of the project.

Luncheon menu, 4 March 1890. Illustrating both the Forth Bridge, and the replacement Tay Bridge, completed in 1887.

A nomination has been made to have the Forth Bridge inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and a decision is expected this summer. Regardless of the outcome, the bridge remains both a remarkable engineering triumph and an iconic part of the Scottish landscape, recognised the world over.

“Imaginative depiction of the Forth Rail Bridge”. This artist’s impression of the completed bridge was included as the title page of Philip Phillips’ The Forth Bridge illustrations, 1886-1887 – Source.

Alison Metcalfe is a curator in the Manuscript and Archive Collections department of the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh. Her varied remit includes archives relating to science and engineering, encompassing collections such as the business archive of the lighthouse-building Stevenson family, the papers of Scottish engineers like John Rennie and Thomas Telford, and of scientists such as Robert Watson-Watt, pioneer of radar technology.

See more public domain photographs from the National Library of Scotland on Wikimedia Commons.

This post is part of our Curator’s Choice series, a monthly feature consisting of a guest article from a curator about a work or group of works in one of their “open” digital collections. Learn more here. See this post in all its full page width glory over at The Public Domain Review.