OpenGLAM progress and potential in Aotearoa New Zealand

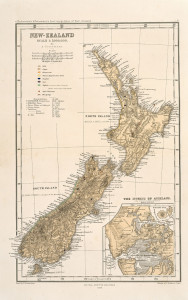

NZ Map, 1864, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, NZ Map 5694. No known copyright.

Aotearoa New Zealand has an oft-repeated saying about itself: “We are a small country; we are far away; we don’t have much money, but this doesn’t stop us from doing significant things.” Sometimes, this is bluster and nation-building rhetoric, but in the case of digital cultural heritage, there is truth to this claim.

New Zealand’s national institutions have been busily digitising their collections for many years (though, the history of digitisation is still remarkably compressed), resulting in impressive (and growing) digitised collections. We have been diligently going about the work of mapping and constructing the framework in which a rich, digital cultural heritage can flourish.

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa’s Collections Online showcases over 200,000 digitised items, and Auckland Art Gallery’s collection is similarly searchable via their website. Outside of the main centres, it is heartening to see that many smaller, regional galleries and museums are also digitising their collections, which are filled with gems and unlikely stories— the most interesting history often happens on the periphery. I recently came across Wanganui Library’s digitised collection, filled with ghostly images of early European settlement on the banks of the Whanganui river.

Carved house, Ohinemutu, George Valentine, 19th century, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. No known copyright restrictions.

As in other countries, the process of digitisation in New Zealand has thrown up knotty problems about copyright and re-use: What do we do about orphaned works? How can we be clear about usage? How do we measure engagement? And what sort of engagement is appropriate? How do we respect the rights of Māori in relation to the digitisation of traditional knowledge, taonga (treasures), and representations of Māori people?

In New Zealand, the copyright term is life of the author plus fifty years—one of the shortest terms for copyright in the English-speaking world. As such, several institutions have led the way by making much of their out of copyright content available for research and re-use by the public. Papers Past, New Zealand’s respected digitised newspaper service, has made its sizeable collection of out of copyright material openly available.

It is interesting to note here that Papers Past’s copyright guide is in line with Dan Cohen’s recent suggestion to “move the attribution from the legal realm into the social or ethical realm by pairing a permissive license with a strong moral entreaty.” The content here is out of copyright, rather than CC0, but is paired with a request that the National Library is acknowledged as the source of information.

Untitled, NZ Truth, 17 December 1925, page 19. Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand. No known copyright.

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, New Zealand’s national museum and art gallery, has recently made the commitment to release 10,000 images per year for the next three years under a ‘no known copyright restrictions’ statement. This framework is taken from the New Zealand Government Open Access and Licensing framework (NZGOAL), a government policy published in 2010, which informs much of the discussion in this sphere. Victoria Leachman, the Rights Advisor at Te Papa comments:

“We see open content as a key way to empower and inspire individuals and communities to use the collections in their own ways. The introduction of open content will also include measures to gauge how people are using online images, recognising that if our digital collections are being re-used, then this will reflect a deeper level of engagement.”

Another recent cross-sector development in the OpenGLAM sphere has been prompted by the First World War centenary. A working group convened by the Ministry for Culture & Heritage is exploring issues around assigning consistent and accurate rights and usage statements to material held by cultural and heritage institutions. They started with a set of copyright-free photographs and film footage taken by Henry Armytage Sanders New Zealand’s official photographer on the Western Front during WW1, and agreed on a consistent statement (adapted from the NZGOAL framework) to clearly indicate that the material has no known copyright restrictions.

H E Wilson (Gunner). Royal New Zealand Returned and Services’ Association: New Zealand official negatives, World War 1914-1918. Ref: 1/2-013427-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

The aim is to provide a discovery tool for openly-licensed WW1 material through the official website for the WW1 centenary programme in New Zealand, WW100.govt.nz (using the Digital New Zealand infrastructure), which starts in August 2014. The photographs by Henry Armytage Sanders will then be available for high resolution download via the respective institutions’ online delivery mechanisms.

In addition, Creative Commons Aotearoa New Zealand has been an important presence in New Zealand since 2006 and has supported several GLAM organisations to release their collections under Creative Commons licenses— especially important for organisations outside of government, where the NZGOAL framework does not apply.

There is still much work to be done however. Many digital collections remain unclear about their usage status. For example, the WWI photography collection by Henry Armytage Sanders had five different usage statements associated with it prior to the Ministry of Culture and Heritage’s project. It is increasingly easy for researchers to search for content online, but difficult to determine whether they can share, re-use, adapt, or annotate the content they have found. Some usage descriptions are vague and applicable only to physical objects rather than digital ones.

DigitalNZ, one of the world’s first country-wide APIs, was established within the National Library of New Zealand in 2008 to address some of these issues and to make New Zealand’s digital content easier to find, share, and use. Like Europeana and the Digital Public Library of America, DigitalNZ is a data aggregator, and currently brings together the digital collections of nearly 150 organisations across the country. As well as providing guidance and advice about digitisation and copyright, DigitalNZ encourages and celebrates the re-use of openly licensed content via the annual Mix & Mash competition.

The National Library of New Zealand is also providing leadership in this area, and is in the final stages of developing its own policy for use and reuse of collection items. The purpose of the policy is to provide a framework of clarity and consistency to both the library and users. It will cover both published and archival items and address some of the complicated issues where frameworks like NZGOAL are silent, for example opening archival items for reuse where the library is not the rights owner, where trust with a donor community is required to be maintained, and where cultural and ethical issues are important considerations for collection items that are out of copyright.

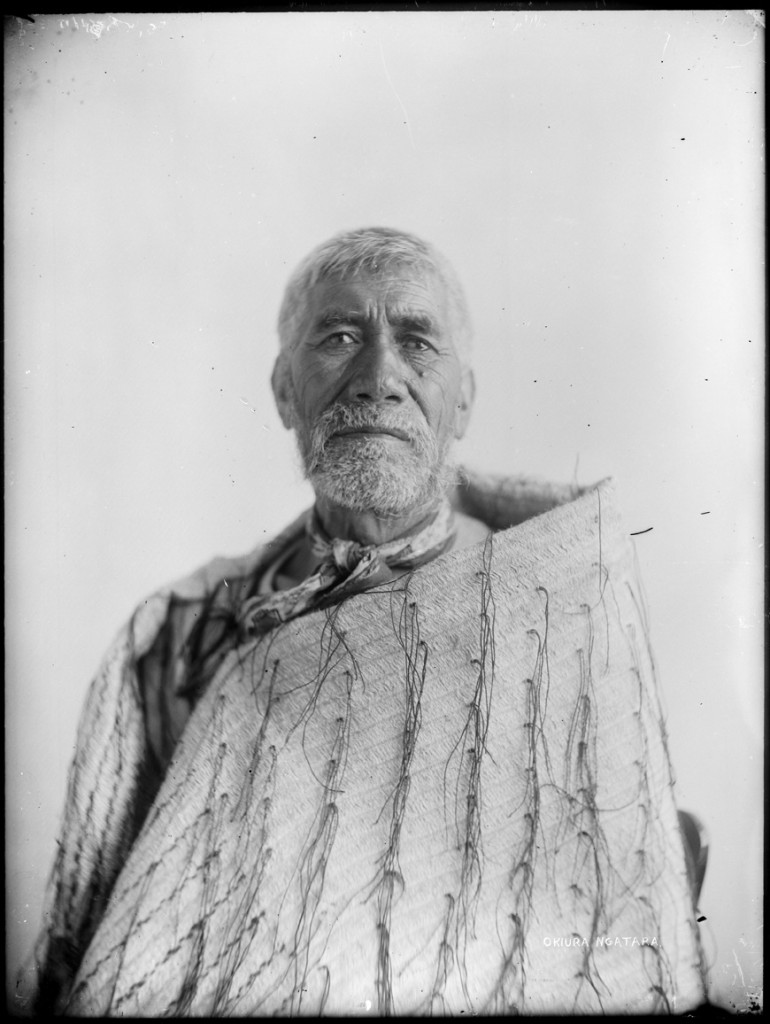

1/2 length portrait of a Maori man, possibly Okiura Ngatara, Auckland Libraries, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 4-7316, no known copyright.

At a recent conference about GLAM cross-sector collaboration, it was noted that in New Zealand, we could look back on the last fifteen or so years as the first wave of digital activity in the GLAM sector, and as a period that could be characterised by large digitisation projects. The next ten years look to be about building networks and adding value to these databases of digital content. I think that in addition to this, the next ten years will be distinguished by negotiating the shifting terrain of copyright, and developing processes in which we can be clear, consistent, and open with our cultural collections.